The Shepherding Community

In the gospel text for Good Shepherd Sunday, Jesus draws upon the auditory interaction between a shepherd and sheep in order to make a point about the relationship between a leader and those she leads.

2 The one who enters by the gate is the shepherd of the sheep. 3 The gatekeeper opens the gate for him, and the sheep hear his voice. [The shepherd] calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. 4 When he has brought out all his own, he goes ahead of them, and the sheep follow him because they know his voice. 5 They will not follow a stranger, but they will run from him because they do not know the voice of strangers” (John 10:2-5).

It's worth noting the context of these statements: Jesus has just healed a blind man, and he is addressing a group of religious leaders about their own forms of spiritual blindness. After the healing and a discussion about its significance, Jesus says to the Pharisees who are present,

39 “I came into this world for judgment, so that those who do not see may see and those who do see may become blind.” 40 Some of the Pharisees who were with him heard this and said to him, “Surely we are not blind, are we?” (John 9:39-40)

And it’s at this point that Jesus commences with the shepherding metaphor, which, perhaps unsurprisingly given their question in verse 40, the Pharisees don't interpret rightly. Their own blindness causes them to miss the significance of his words.

The source of their confusion is not about the metaphor itself, however. Shepherding, besides being a well known occupation in the first-century world, was also an often used metaphor in the Old Testament for leadership—a “shepherd” is a powerful king who can defend the sheep, or a wise ruler who knows what the sheep need.

A lengthy passage in Ezekiel 34 uses the metaphor in this way. The Pharisees aren’t confused by the metaphor itself, but rather who the metaphor's referents are. They would have agreed with Jesus that bad shepherds are bad. They would have picked up on how Jesus’ metaphor is an allusion to the same language used by the prophets. So when John says in v. 6 “but the Pharisees did not understand what he was saying to them,” he’s alerting his readers to the fact that the Pharisees fail to consider how they themselves might be thieves, bandits, and strangers Jesus mentions in John 10.

The aforementioned passage from Ezekiel 34 begins with a prophetic condemnation of such figures masquerading as shepherds.

“The word of the Lord came to me… Woe, you shepherds of Israel who have been feeding yourselves! Should not shepherds feed the sheep?” (Ezekiel 34:1-2).

If the bad shepherds are those who put their own appetites above those of the sheep, what does a Good Shepherd do? Further down, Ezekiel prophesies,

11 “For thus says the Lord God: I myself will search for my sheep and will sort them out. I will rescue them from all the places to which they have been scattered on a day of clouds and thick darkness…. 14 I will feed them with good pasture, and the mountain heights of Israel shall be their pasture; there they shall lie down in good grazing land, and they shall feed on rich pasture on the mountains of Israel. 15 I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep, and I will make them lie down, says the Lord God. 16 I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strays, and I will bind up the injured, and I will strengthen the weak…” (Ezekiel 34:11, 14-16).

There’s a clear contrast here between the shepherding styles.

We see a specific example of how this contrast in shepherding styles plays out in Luke’s description of the early community of believers. It’s perhaps noteworthy that different lectionaries feature New Testament readings for Good Shepherd Sunday from either Acts 2:42-47 or Acts 6:1-9 . In these texts, Luke provides a picture of the rhythms of life (and their occasional disruption) among the earliest believers.

Consider this description of their life together alongside the shepherd imagery from John 10 and Ezekiel 34:

42 They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers. 44 All who believed were together and had all things in common; 45 they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need. 46 Day by day, as they spent much time together in the temple, they broke bread at home and ate their food with glad and generous hearts… (Acts 2:42-46).

This community is well shepherded. They stay together. The injured among them are being bound up. They’re resting in the lush pasture of healthy relationships. They experience provision.

Not only is this community well shepherded, but they are also shepherding each other. Luke paints a picture of the church itself as a shepherding community. The church can never take the place of the good shepherd, but the church can imitate the good shepherd in its treatment of others.

Conversely, we would do well to consider Jesus’ challenge to the Pharisees as a word of warning directed at us, His body.

The counterexample to this depiction of a well-shepherded community comes in Acts 6 when widows among the early believers are being overlooked in the serving of food.

Now during those days, when the disciples were increasing in number, the Hellenists complained against the Hebrews because their widows were being neglected in the daily distribution of food (Acts 6:1).

Perhaps you’ve noticed the abundance of images related to food, from the starving sheep in Ezekiel 34 to the lush pasture in John 10 to the shared table in Acts 2 and the inequities in food distribution in Acts 6.

Given what we’ve looked at thus far, we might say that shepherding well or poorly hinges on how well we can imitate the good shepherd in nourishing one another.

How can we offer nourishment to one another? Eating together is a good place to start. Beyond that, we would do well to consider how our own words to one another can help to make the voice of the good shepherd recognizable to us.

I don’t know about you, but I’m struck by the responsibility this entails. Our words have such weight, not only because they affect others’ self-conceptions, but also because through our words, we’re attuning each other’s ears to hear the nourishing words of the good shepherd.

How, then, can our voices make the voice of the good shepherd recognizable?

Conversely, how might our voices drown out the voice of the good shepherd?

Adopting the persona of the speaker in the opening line of Psalm 23 situates us rightly. “The Lord is my shepherd.” Being shepherded by God must shape my self-understanding. To put it another way, I will have a difficult time sharing with others what I don’t experience on a regular basis. If I refuse nourishment from Christ and his body, the Church, then the Scriptures we’ve considered above point to two potential outcomes: Either I will starve, or I will try to acquire nourishment elsewhere on my own and for myself.

Along this same line, it’s perhaps telling that Paul’s instruction in 1 Corinthians 11 regarding the institution of Lord’s Supper begins with the words,

“For I received from the Lord that which I also passed on to you…” (1 Corinthians 11:23).

Embedded in the institution of the Lord’s Supper, the same meal that Jesus enjoins his followers to share regularly, is that it is both received and passed on. To experience the former without the latter is to shepherd poorly.

Paul confronts this tendency among the Corinthian church to receive without passing on. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his characterization of the church’s gatherings sounds very much like the description of the bad shepherds in Ezekiel 34:

17 Now in the following instructions I do not commend you…. 20 When you come together, it is not really to eat the Lord’s supper. 21 For when the time comes to eat, each of you proceeds to eat your own supper, and one goes hungry and another becomes drunk (1 Corinthians 11:17a, 20-21).

In his book Worship in the Early Church, historian and theologian Justo Gonzalez cites a number of early texts about the practice of communion among early believers and offers the following conclusion: “The center of [receiving communion] is not that the individual is fed, but rather that the community as a whole is nourished.”

With this characterization in mind, we might reconsider our own place within the metaphor Jesus presents in John 10. We are the sheep passing through the gate toward nourishment in the pasture, but we are also the gatekeepers, opening the way toward nourishment. We are to imitate the good shepherd in our speech to each other so that his voice might become recognizable in others’ ears.

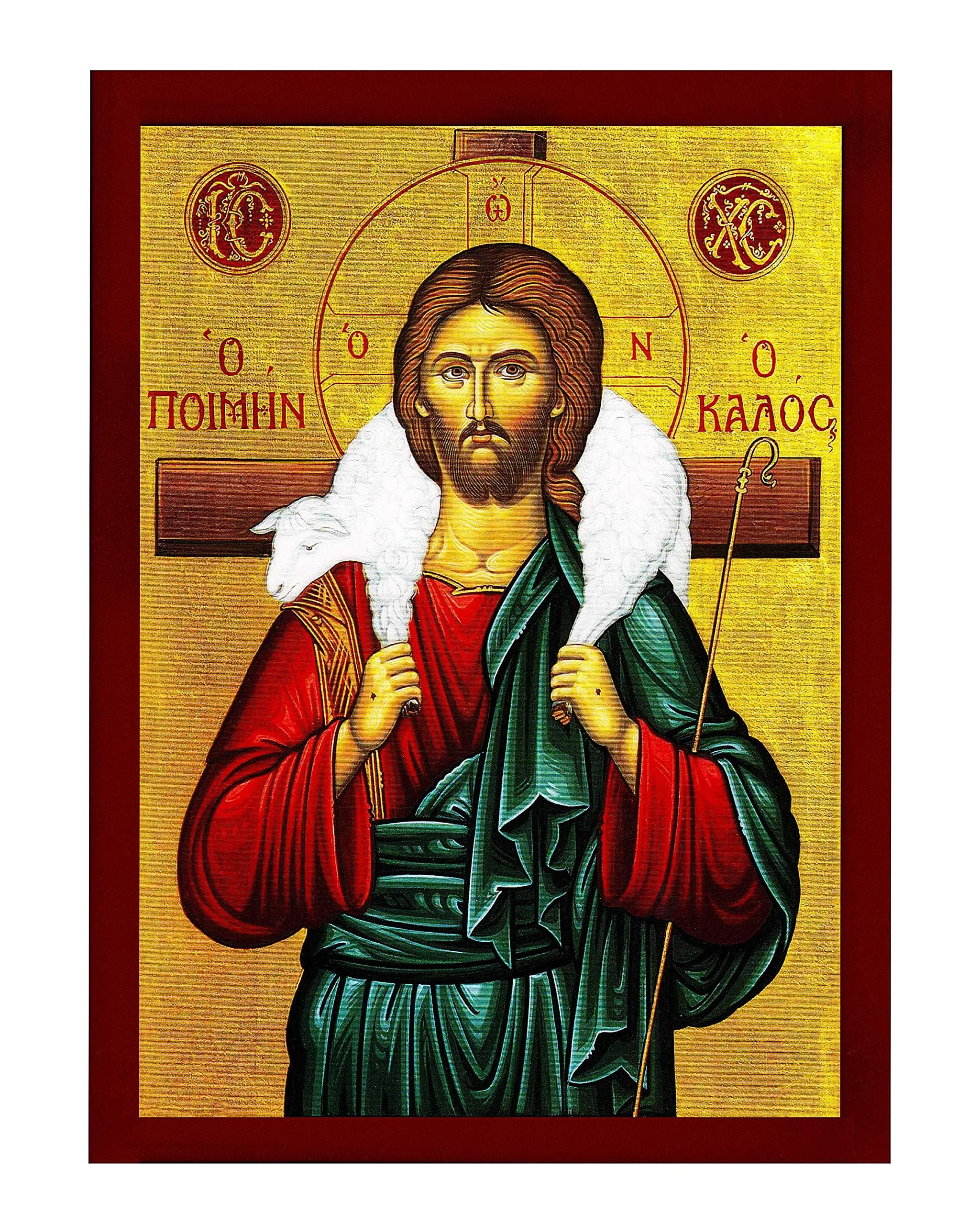

This reading of the early believers in Acts 2 as a shepherding community invites not only invites us to read John 10 with fresh eyes, but also to reassess our role in the scene depicted in the icon of the good shepherd. Where are we in this icon? In one sense, it’s fairly straightforward: we are the cared-for sheep, those whom the good shepherd leaves the fold to rescue.

With the words Ezekiel 34 echoing in our ears, we are also challenged to see ourselves reflected in the image of the one whose shoulders bear not only a wayward sheep, but also a wooden beam. The face we meet reminds us of our crucial task to shepherd as we have been shepherded.