A Reflection on Henry Ossawa Tanner's "Flight Into Egypt"

1.

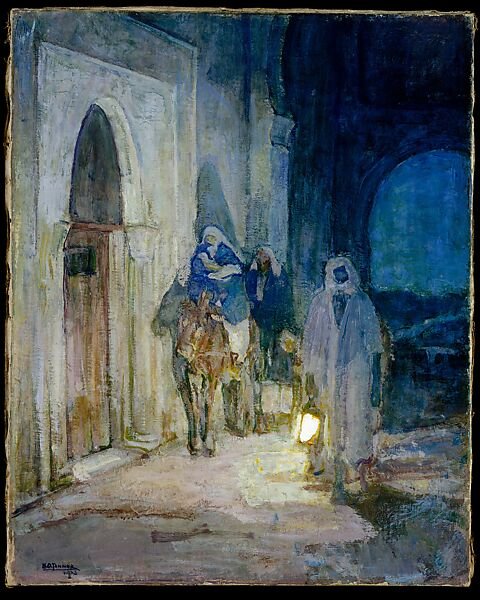

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s 1923 painting, “Flight Into Egypt” depicts the holy family’s journey from Bethlehem to Egypt described in Matthew 2:13-15.

13 Now after they had left, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you, for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.” 14 Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt 15 and remained there until the death of Herod. This was to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet, “Out of Egypt I have called my son.”

Tanner’s painting presents several intriguing details not explicitly present in the text. Perhaps the most noticeable is the light in the foreground, which suggests a connection between the journey of the Magi toward Bethlehem with the journey of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus away from Bethlehem.

Tanner depicts an unknown figure lighting the way for the holy family. The light this figure holds is reminiscent of the mysterious star that guides the Magi to Bethlehem earlier in Matthew 2. While we might picture the Magi with upturned faces toward the star, Tanner depicts the holy family following a light held close to the ground that they might avoid detection.

Heightening the irony, Mary holds Jesus in her arms, obscuring him from view. In Tanner’s scene, the light of revelation to the gentiles is shrouded in darkness. Shortly after the Magi travel a great distance to worship the child, Mary and Joseph go to great lengths to conceal him.

The dim light in the painting adds a layer of complexity to the Old Testament reading assigned for Epiphany, in which Isaiah prophesies,

Arise, shine, for your light has come,

and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you.

2 For behold, darkness shall cover the earth,

and thick darkness the peoples;

but the Lord will arise upon you,

and his glory will be seen upon you.

3 And nations shall come to your light,

and kings to the brightness of your rising.

Tanner invites viewers to reflect upon a truth that is otherwise easy to miss: Before Jesus proclaims himself as the light of the world, his mother flees with him under the cover of darkness. Before Jesus rides into Jerusalem as king, he’s smuggled out of Bethlehem as a fugitive.

2.

Christian singer and songwriter Rich Mullins released a song in 1998 titled “My Deliverer.” In it, Mullins suggests Jesus’ entrance into Egypt constitutes God’s direct response to the cries of the enslaved Israelites who suffered under Pharaoh centuries prior.

Joseph took his wife and her child and they went to Africa

To escape the rage of a deadly king

There along the banks of the Nile, Jesus listened to the song

That the captive children used to sing, they were singing,

‘My Deliverer is coming. My Deliverer is standing by’

These deceptively simple lines accomplish more than a mere retelling of the holy family’s flight into Egypt. The song creatively ties together God’s salvation of Israel from slavery with God’s sending Jesus to rescue the world from its captivity to sin and death. God, ever attentive to the suffering of his people, now answers them in Jesus.

To be sure, Mullins’ song packs a punch theologically. But if we listen closely, perhaps the most challenging aspect of the song is the scandalous truth to which it gestures: the deliverance Jesus brings is incomplete unless it includes Egypt.

The phrase “captive children” not only calls to mind the suffering of the enslaved Israelites, but also hints at the suffering throughout Egypt upon the death of the firstborn. According to this reading, Egypt herself was held captive and in need of a deliverer. Thus, the Christ child’s arrival in Egypt foreshadows what the Church celebrates at Epiphany: Jesus has been made known both to Israel and Egypt, Jew and Gentile.

Christ enters Egypt as its long-awaited deliverer, beckoning them to join the chorus of hopeful longing that Israel once sang there.

3.

Throughout the early chapters of Matthew, the gospel writer alludes to Moses, the Exodus narrative, and Israel’s deliverance from slavery in Egypt. Early Christians were quick to pick up on this thread, expounding upon the significance of Jesus’ entrance into Egypt as effecting an all-encompassing rescue mission.

Chromatius, a Fourth Century Bishop from Italy, reimagines Egypt’s role in salvation history in his Tractate on Matthew:

“After Egypt's ancient, grave sin, after many blows had been divinely inflicted upon it, God the omnipotent Father, moved by devotion, sent his Son into Egypt. He did so that Egypt, which had long ago paid back the penalty of wickedness owed under Moses, might now receive Christ, the hope of salvation. Egypt, which of old under Pharaoh stood stubborn against God, now became a witness to and home for Christ.”

An anonymous source from the early centuries of the church echoes Chromatius, noting, “Just like a doctor, the Lord went down into Egypt that he might visit it as it languished in error, not that he might stay there. For at first blush it seems as if he went down into Egypt in flight from Herod. The fact is that he went in order to put to flight the demons of Egypt’s error.

These passages suggest that Jesus comes to the place from which God had delivered Israel that he might also deliver Egypt. In other words, he comes not only to Egypt, but for Egypt. He enters Egypt as the light of revelation to the gentiles. Jesus is on mission from the very beginning.

St. Peter Chrysologus, a fifth century church father, offers the most concise of these interpretations. He says simply, “Christ fled for us, not for himself.”

These imaginative meditations on the flight to Egypt from early Christians reveal with stunning clarity a truth we celebrate at Epiphany: In hiding Jesus from the powers that seek his life, Mary simultaneously bears him to the world. This mystery is perhaps best expressed in the prologue to John’s gospel: The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness does not overwhelm it.

Epiphany offers a light, however dim, that we might wonder anew at the grace available to those who walk in the valley of the shadow of death. For even there, beyond the limits of our imagining, Jesus ventures to deliver us.

Listen: you came to us as one of us

and lived with us and died for us and descended into hell for us

and burst out into life for us:

Do you now hold Pharaoh in your arms?

Madeleine L’Engle, “Pharaoh’s Cross”